J'aime boire du thé avec tous les gens qui aiment boire le thé, et cela quelque soit leur origine, leur religion, leur convictions politiques, leurs habitudes alimentaires, sexuelles... Partager le plaisir d'une bonne coupe de thé est un tel acte de fraternité que je n'aime pas le gâcher par des sujets qui divisent.

Aussi, en règle général, je n'aime pas trop la confusion des genres et ce mouvement de politisation tout azimut. Je n'ai pas envie que le thé soit de droite ou de gauche ou du centre ou des extrêmes. Le thé doit rester la boisson universelle de tous. J'écris donc ces lignes sans sectarisme et sans désir de politiser ma boisson favorite.

Néanmoins, je trouve que l'histoire du thé nous permet de mieux comprendre les grands enjeux de notre humanité. Prenons le thé durant la dynastie Song (960-1279). La Chine était alors au faîte de sa gloire. Prospère et instruite, la Chine d'alors était technologiquement bien supérieure aux autres nations.

Que se passa-t-il alors avec le thé? Durant la dynastie Tang qui précéda, les feuilles de thé vert étaient broyées, mais moins finement, et simplement cuites quelques secondes dans un chaudron, avec un peu de sel, avant qu'on ne partage cette boisson dans des bols plus petits.

La méthode Song va vers plus de finesse:

- pour faire le thé en poudre matcha, on ne récolte que les bourgeons, la partie la plus concentrée et qualitative de la plante. Agriculture bio et raisonnée. Transport facilité.

- Tout est bu: zéro déchet.

- la méthode de préparation est personnalisée: chacun son bol. Indivualisme au sein de la tradition.

- le fouet en bambou permet de faire ressortir la mousse du thé, le côté le plus onctueux et délicieux de ce thé. Plaisir.

- Quand on a tout bu, il reste le plaisir d'admirer les variations chromatiques de noir et de brun. La beauté du bol Jianyang est simple et moderne, mais profonde à la fois. Art.

Le thé de la Chine des Song montre la voie comment évoluer dans un monde de plus en plus riche. La réponse, c'est plus de qualité et moins de quantité. L'enjeu est de faire en sorte que la baisse de quantité est plus que compensée par une hausse de qualité. On peut alors continuer à parler de progrès. C'est le cas quand le plaisir augmente plus que le prix, par exemple. Pour cela, il faut avoir un palais sensible et expérimenté.

L'exemple venait du haut. L'empereur Song Huizong ne fit pas une loi, mais écrivit un traité du thé qui permet de propager cette méthode de préparation par l'exemple et le désir plutôt que par la coercition.

J'espère que ces quelques reflexions ne vous auront pas apparu trop 'politiques'. Ceci n'est pas un non plus appel à ne boire que du matcha ou bien à monter en gamme dans vos thés si vous êtes étudiant et n'arrivez pas à boucler vos fins de mois! Ce sont juste quelques reflexions sur les parallèles entre nos problématiques alimentaires et économiques actuelles et le thé de la dynastie Song.

Etudier le thé des Song, c'est contempler la voie d'un avenir radieux et raffiné pour l'humanité!

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Friday, June 23, 2017

The 2017 Chinese Porcelain Exhibition of the Tea Institute at Penn State. Day 3: black glazed bowls

The third day's subject were black glazed bowls from the Song dynasty (960-1279). The Song emperor had his made in Jianyang, in Fujian. But being popular at the court, they were made/reproduced all over China. Sometimes the kiln can be determined from the shape, design of the bowl, but the best way is to look at the unglazed foot. A lighter clay indicates a northern kiln, while the original Jianyang clay would be rich in iron oxide and therefore dark/red.

The beauty of the black glaze comes from its apparent simplicity (1 color: black) that contains with so many fine variations: hare's fur (see the modern bowl in the picture) or partridge feathers when the spots are round or lion fur when the bowl turns almost completely brown. These variations were difficult to control when the bowls were fired in saggars in long dragon kilns. The failure rate was very high, but the best pieces are amazing. Song black glaze almost as modern and abstract as Malevich's Black Square! In the many shades of black there's so much more to see than animal fur...

In the afternoon, Teaparker's student Nancy demonstrated a Song dynasty style brewing for the first time on the American continent!

But before I come to it, let's look at the Jianyang bowl more in detail. There were several possible shapes for the bowl, but they were all designed taller, less shallow than Tang dynasty bowls. This was a practical matter, because if you whisk tea in a shallow bowl it will spill outside easily. A small foot is more elegant, but less stable. That's why the center of gravity is lowered by making the base thicker than the top. Then, there's the strange fact that the glaze stops above the foot (instead of trying to cover it). This is actually made on purpose as an indication for how little tea powder should be put at the bottom of the bowl. And finally, you may also notice that the top of the bowl is not evenly curved. 1 cm below the rim approximately there's a change in the shape. This is also some kind of visual clue for the brewer/whisker: that's where the limit for the pouring the water.

The Song dynasty technique was recorded by emperor Song Huizong (1082-1135) in his Treatise on tea, but this tea whisking tradition was discontinued in China. Teaparker is one of the rare tea scholars to have revived the original technique.

The Tea Institute at Penn State also has a group devoted to learn the Japanese Chanoyu (Omotesenke and Urasenke schools). Its members could see that the Song tea technique is different from what they are practicing, even if the matcha used is the same.

The key differences are:

- using an ewer to pour the water in the bowl while whisking at the same time,

- a lot of whisking and more water to create a thick layer of foam (like a cappuccino).

We then had students prepare the tea using the Japanese technique (less whisking and less water). Guess what style the great majority of the participants preferred? The Sung dynasty style way, because it didn't taste bitter, but smooth and harmonious.

An interesting discussion followed about the differences between the Chinese and the Japanese approach. At the very start of this discussion, Teaparker told the audience that he has the greatest respect for the longevity of Japan's Chanoyu. Unlike the Chinese, the Japanese were able to preserve their tradition until now. Without this big accomplishment, it wouldn't be possible to revive the Song dynasty tea tradition today. The Japanese were quite creative in adapting elements of Tang and Song to make it their own. However, in the process of establishing a beautiful and polite ritual, they lost sight of the essential concept: producing a good tasting bowl of tea. The tea students explained that the bitterness of the tea is a symbol for the human condition and our hard lives. But for Teaparker, this is just a bad excuse. Yes, life may be hard, but when we brew tea we seek pleasure. The goal of brewing is always tea happiness!

After this class, the Tea Institute had a little ceremony to name their tea house after Teaparker. This honor recognizes all the knowledge, expertise... that Teaparker has contributed to the Tea Institute over the last 6 years. And we hope this will continue for many more years!

After the event, we had several tea tastings during the master class (reserved for Tea Institute members). We tasted several WuYi Yan Cha and Teaparker taught the students how to smell and identify if a Yan Cha was made with several different cultivars.

We also had a proper Yan Cha that felt so amazing that just a few drops per cup were enough to enjoy and feel the difference!

On this Satuday night, State College was full of parties as there was a special blue on white football game. That's when State College's defense and offense teams play against each other. Many alumni came back to town for this event and the bars were all full with long lines in front of each.

The Tea Institute members couldn't care less! Most came back to the Teaparker Tea House after dinner for our nightly Chaxi!

Tatum brewed with Mahler's 5th symphony in background. This proved too relaxing for Jason! He missed some excellent roasted Oolong in the process...

We started the event at 10 AM and at 11:30 PM we were still brewing tea, kind of hoping all this tea pleasure would never stop!

Reminder: please place your tea orders on tea-masters.com now (before June 29) as I'll be off the whole month of July.

The beauty of the black glaze comes from its apparent simplicity (1 color: black) that contains with so many fine variations: hare's fur (see the modern bowl in the picture) or partridge feathers when the spots are round or lion fur when the bowl turns almost completely brown. These variations were difficult to control when the bowls were fired in saggars in long dragon kilns. The failure rate was very high, but the best pieces are amazing. Song black glaze almost as modern and abstract as Malevich's Black Square! In the many shades of black there's so much more to see than animal fur...

|

| Jianyang bowl from the Met museum in NYC |

But before I come to it, let's look at the Jianyang bowl more in detail. There were several possible shapes for the bowl, but they were all designed taller, less shallow than Tang dynasty bowls. This was a practical matter, because if you whisk tea in a shallow bowl it will spill outside easily. A small foot is more elegant, but less stable. That's why the center of gravity is lowered by making the base thicker than the top. Then, there's the strange fact that the glaze stops above the foot (instead of trying to cover it). This is actually made on purpose as an indication for how little tea powder should be put at the bottom of the bowl. And finally, you may also notice that the top of the bowl is not evenly curved. 1 cm below the rim approximately there's a change in the shape. This is also some kind of visual clue for the brewer/whisker: that's where the limit for the pouring the water.

The Song dynasty technique was recorded by emperor Song Huizong (1082-1135) in his Treatise on tea, but this tea whisking tradition was discontinued in China. Teaparker is one of the rare tea scholars to have revived the original technique.

The Tea Institute at Penn State also has a group devoted to learn the Japanese Chanoyu (Omotesenke and Urasenke schools). Its members could see that the Song tea technique is different from what they are practicing, even if the matcha used is the same.

The key differences are:

- using an ewer to pour the water in the bowl while whisking at the same time,

- a lot of whisking and more water to create a thick layer of foam (like a cappuccino).

We then had students prepare the tea using the Japanese technique (less whisking and less water). Guess what style the great majority of the participants preferred? The Sung dynasty style way, because it didn't taste bitter, but smooth and harmonious.

An interesting discussion followed about the differences between the Chinese and the Japanese approach. At the very start of this discussion, Teaparker told the audience that he has the greatest respect for the longevity of Japan's Chanoyu. Unlike the Chinese, the Japanese were able to preserve their tradition until now. Without this big accomplishment, it wouldn't be possible to revive the Song dynasty tea tradition today. The Japanese were quite creative in adapting elements of Tang and Song to make it their own. However, in the process of establishing a beautiful and polite ritual, they lost sight of the essential concept: producing a good tasting bowl of tea. The tea students explained that the bitterness of the tea is a symbol for the human condition and our hard lives. But for Teaparker, this is just a bad excuse. Yes, life may be hard, but when we brew tea we seek pleasure. The goal of brewing is always tea happiness!

After this class, the Tea Institute had a little ceremony to name their tea house after Teaparker. This honor recognizes all the knowledge, expertise... that Teaparker has contributed to the Tea Institute over the last 6 years. And we hope this will continue for many more years!

After the event, we had several tea tastings during the master class (reserved for Tea Institute members). We tasted several WuYi Yan Cha and Teaparker taught the students how to smell and identify if a Yan Cha was made with several different cultivars.

We also had a proper Yan Cha that felt so amazing that just a few drops per cup were enough to enjoy and feel the difference!

On this Satuday night, State College was full of parties as there was a special blue on white football game. That's when State College's defense and offense teams play against each other. Many alumni came back to town for this event and the bars were all full with long lines in front of each.

The Tea Institute members couldn't care less! Most came back to the Teaparker Tea House after dinner for our nightly Chaxi!

Tatum brewed with Mahler's 5th symphony in background. This proved too relaxing for Jason! He missed some excellent roasted Oolong in the process...

We started the event at 10 AM and at 11:30 PM we were still brewing tea, kind of hoping all this tea pleasure would never stop!

Reminder: please place your tea orders on tea-masters.com now (before June 29) as I'll be off the whole month of July.

Thursday, June 22, 2017

Spring 2017 Alishan Jinxuan Oolong

This April 16th, 2017 Jinxuan Oolong from Alishan is the most most affordable high mountain Oolong in my selection this year. While it's an excellent gift choice for Oolong beginners, it's also a nice everyday fresh tea for experienced drinkers.

I still tend to eat and drink great food or tea on special occasions only. Drinking Da Yu Ling or Lishan Oolong every day would end up being boring, I feel. Call me a reasoned Epicurean! Or maybe it's because I'd feel guilty to indulge in the very best teas every day?!

But no matter the tea that is on the menu, it's always the same question: how do I get the most of these leaves? How do I make this moment the most meaningful?

My answer for this tea is summed up in this 'Refreshing Waves' Chaxi!

This round zhuni teapot makes a great job unfolding the leaves and releasing all the light aromas of this Jinxuan. If you have a great tool to improve your tea, it feels right to use it!

Jinxuan and qingxin Oolong are 2 different cultivars with different characters. If you're used to drinking High mountain Oolong made from qingxin Oolong leaves, this Jinxuan will feel lighter in taste with different fragrances. To enjoy it, you need to adjust your expectations. When you go to a guitar concert, you don't expect it to hear the sounds of a violin! While there are the similarities coming from the Alishan climate and soil, the Jinxuan cultivar has its own, lighter, character.

This lightness is actually a good match with the high mountain spring freshness of this tea. It's a simple pleasure, but very satisfying nonetheless.

And I feel my Chaxi has well captured the spirit of AliShan and its diverse vegetation!

Note: Place your order until June 29th (preferably a little bit earlier) before my month long holiday in Europe in July.

I still tend to eat and drink great food or tea on special occasions only. Drinking Da Yu Ling or Lishan Oolong every day would end up being boring, I feel. Call me a reasoned Epicurean! Or maybe it's because I'd feel guilty to indulge in the very best teas every day?!

But no matter the tea that is on the menu, it's always the same question: how do I get the most of these leaves? How do I make this moment the most meaningful?

My answer for this tea is summed up in this 'Refreshing Waves' Chaxi!

This round zhuni teapot makes a great job unfolding the leaves and releasing all the light aromas of this Jinxuan. If you have a great tool to improve your tea, it feels right to use it!

Jinxuan and qingxin Oolong are 2 different cultivars with different characters. If you're used to drinking High mountain Oolong made from qingxin Oolong leaves, this Jinxuan will feel lighter in taste with different fragrances. To enjoy it, you need to adjust your expectations. When you go to a guitar concert, you don't expect it to hear the sounds of a violin! While there are the similarities coming from the Alishan climate and soil, the Jinxuan cultivar has its own, lighter, character.

This lightness is actually a good match with the high mountain spring freshness of this tea. It's a simple pleasure, but very satisfying nonetheless.

And I feel my Chaxi has well captured the spirit of AliShan and its diverse vegetation!

Note: Place your order until June 29th (preferably a little bit earlier) before my month long holiday in Europe in July.

Tuesday, June 20, 2017

La beauté des Oolongs

Il m'est facile de répondre à la question: "Quelle famille de thé emporterais-tu sur une ile déserte si tu ne pouvais qu'emmener des thés d'une seule famille?" Du Oolong, évidemment! C'est le thé le plus divers.

Les Oolongs de haute montagne ont la fraicheur et finesse du thé vert. Les Hung Shui ont des notes complexes dues à leur torréfaction (parfois comme du café ou de la noisette). Avec les Beautés orientales, on a des arômes mielleux et fruités parfois similaires au thé rouge. Chez les Oolongs âgés on retrouve l'impact du vieillissement et des notes de bois et d'encens typique des puerhs! Et quand on déguste une Beauté Orientale, traditionnellement torréfiée, et vieillie (comme sur ces photos), alors on a un peu de tout cela concentré dans sa coupe! Quelle finesse et quel régal!

Dire qu'on aime le Oolong, c'est une réponse de Normand! Il y en a pour tous les goûts et toutes les couleurs chez les Oolongs. Vert/jaune, or, orange foncé, brun, voire noir, on trouve toutes ces couleurs dans les infusions d'Oolong!

Cette diversité provient d'une grande latitude dans le degré d'oxydation, de torréfaction et d'âge des Oolongs. C'est ce qui rend leur production plus difficile que les autres thés. Les Oolongs ne sont pas unidimensionnels, mais sont toujours une recherche d'un équilibre du degré d'oxydation et de torréfaction. Et si l'on rajoute les divers cultivars, terroirs, saisons et climats, on arrive à une complexité étonnante, voire déroutante.

Le livre le mieux fait ne saurait jamais décrire tous les Oolongs qu'on peut trouver. Il y aura toujours des innovations (comme les zhuo yan qui ont apparu dans ma boutique depuis l'automne passé.) Et à quoi cela servirait-il de lister tous ces thés si l'on n'arrive pas à les trouver en Europe? Ou si leur description est incomplète ou erronnée?

Note: Passez vos commandes sur tea-masters jusqu'au 29 juin au plus tard pour profiter de la fraicheur des toutes nouvelles récoltes d'Oolong Taiwanais. (Ou bien attendez mon retour à Taiwan en août.)

Les Oolongs de haute montagne ont la fraicheur et finesse du thé vert. Les Hung Shui ont des notes complexes dues à leur torréfaction (parfois comme du café ou de la noisette). Avec les Beautés orientales, on a des arômes mielleux et fruités parfois similaires au thé rouge. Chez les Oolongs âgés on retrouve l'impact du vieillissement et des notes de bois et d'encens typique des puerhs! Et quand on déguste une Beauté Orientale, traditionnellement torréfiée, et vieillie (comme sur ces photos), alors on a un peu de tout cela concentré dans sa coupe! Quelle finesse et quel régal!

Dire qu'on aime le Oolong, c'est une réponse de Normand! Il y en a pour tous les goûts et toutes les couleurs chez les Oolongs. Vert/jaune, or, orange foncé, brun, voire noir, on trouve toutes ces couleurs dans les infusions d'Oolong!

Cette diversité provient d'une grande latitude dans le degré d'oxydation, de torréfaction et d'âge des Oolongs. C'est ce qui rend leur production plus difficile que les autres thés. Les Oolongs ne sont pas unidimensionnels, mais sont toujours une recherche d'un équilibre du degré d'oxydation et de torréfaction. Et si l'on rajoute les divers cultivars, terroirs, saisons et climats, on arrive à une complexité étonnante, voire déroutante.

Le livre le mieux fait ne saurait jamais décrire tous les Oolongs qu'on peut trouver. Il y aura toujours des innovations (comme les zhuo yan qui ont apparu dans ma boutique depuis l'automne passé.) Et à quoi cela servirait-il de lister tous ces thés si l'on n'arrive pas à les trouver en Europe? Ou si leur description est incomplète ou erronnée?

Note: Passez vos commandes sur tea-masters jusqu'au 29 juin au plus tard pour profiter de la fraicheur des toutes nouvelles récoltes d'Oolong Taiwanais. (Ou bien attendez mon retour à Taiwan en août.)

Friday, June 16, 2017

Da Yu Ling, spring 2017

|

| View from a plantation on Da Yu Ling |

|

| DYL 95K, spring 2017 |

The locations of the various Da Yu Ling plantations are identified by the kilometer number of this road. For reference, the village of Lishan starts at 82K and finishes around 84K on this road. The Da Yu Ling starts further up. And since the road is ascending at this place, the highest plantations are generally located at the higher numbers. That's why 95K is higher and more expensive than 90K, for instance.

At an elevation of over 2000 meters above sea level, it's easy to feel light-headed and slightly dizzy. I wonder if the tea leaves also 'feel' this, because they are able to convey this mountain feeling in the brew!

Da Yu Ling is not the only mountain where qingxin Oolong grows over 2000 meters. It became famous because that's where the highest plantation was located (reaching 2650 meters), but this one has been uprooted. But its fame isn't just simply a record elevation. For high mountain Oolong lovers, this fame is now rooted in the quality of its aromas.

Da Yu Ling Oolong manages the difficult task of combining the power/energy of the high mountain with finesse and purity. With most of the other mountains you have either one or the other.

With Da Yu Ling you can get both! It's a memorable experience for all Oolong drinkers.

Wednesday, June 14, 2017

The 2017 Chinese Porcelain Exhibition of the Tea Institute at Penn State. Day 2: Dehua

This year, we witnessed the recent improvements to the design of the Tea Institute at Penn State. The entrance of the tea room is stunning thanks to these 2 wonderful displays of the Tea Institute's tea wares.

Some of these remarkable wares are over a hundred years old! What I like is that they are not just meant to be admired, but they are still being used on special occasions!

On the second Day of this event, the Tea Institute showed its gratitude to its founder, Jason Cohen, by naming this Gallery of Asian Art after him. Samuel Li, the current director, gave the sign to Jason next to his delighted parents.

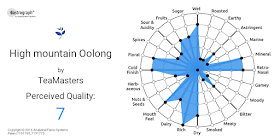

Jason Cohen graduated a few years ago and has now moved to NYC with the startup company he has founded, Gastograph, that specializes in analytical flavor systems. It aims at using rational measurements to taste and aromas of a big range of food and beverages (chocolate, coffee, beer, wine... and tea).

This is what their tool looks like when I use it to describe my latest Da Yu Ling 95K High Mountain Oolong from spring 2017:

I made this with the free App that exists both for Android and iOS. (Search: Gastograph) It can be a helpful tool to analyze the flavors of the tea, putting words and concepts on your feelings and remembering your experience. So, as you can see, Jason's company is deeply rooted in his Chinese tea tasting experience and his engineering background! And even if most of his customers are beer breweries and coffee makers, Jason continues to brew tea the same as he innovates, fearlessly: so many cups and such a little teapot!

During the first day, we learned that the Chinese achieved the first porcelain wares during the Eastern Han dynasty some 2000 years ago. The technique continued to improve with time. After the Eastern Jin (265-420), kilns in Jiangxi invented the saggar. Saggars are flame-resistant containers that protect the porcelain ware during the firing. This gives them a nicer and more even gloss and keeps the porcelain almost spotless.

White ceramics developed mostly in the North of China (ex: Ding ware from Hebei), but the climax of white porcelain was achieved in the south, in the kilns of Dehua in Fujian Province during the late Ming/early Qing period. French historian Albert Jacquemart (1808-1875) coined the term 'Blanc de Chine' (white from China) to call Dehua porcelain, a sign of Dehua's fame.

While we're focusing our study on porcelain tea cups, Dehua was actually even more famous for its sculptures of deities (ex: Guanyin with or without child).

This tall cup is a good example of the ivory (lard) hue of Dehua porcelain. The porcelain is rather thin and allows for the light to shine through the body. This reveals then a finely calligraphied Chinese poem!

This touches to key concepts of Chinese beauty dating back to the Sung dynasty: simplicity, refinement and purity. At first sight, the cup doesn't look that special, especially now that porcelain production has been industrialized. But instead of showing off the beauty of the calligraphy by painting with color, the artist chose to make it transparent and only visible under a direct light.

And, most amazingly, the tea tasted different when it had been poured from this cup. The taste was smoother, more refined and deeper. We could have used the Gastograph app to measure and analyze the difference! All the participants felt it. But it was no miracle or magic, just the result of using an antique cup made with natural ingredients, rested clay, wood fired in kilns with multiple chambers. For all these reasons, Dehua cups have the best impact on many teas (and Wuyi Yan Cha in particular) and we were lucky to experience it!

When we are dealing with antique cups, it's not always obvious if they were used for wine or for tea. Teaparker explained that wine experts often conclude that the cups they study were used to drink wine, while tea experts believe the same cups were used to drink tea.

This small Dehua cup gives us a better explanation: most of such cups had dual use for wine and tea. We have proof for this in this cup: the characters Jiu and Cha were both written on the same cup!

Like on day 1, most of us came back to the tea room after dinner to continue brewing tea almost until midnight! I think one of the teas we had was my spring 2017 top Oolong from Long Feng Xia on Shan Lin Xi. This mountain has a very understated, sweet and refined aroma. A good match for Dehua porcelain!

Some of these remarkable wares are over a hundred years old! What I like is that they are not just meant to be admired, but they are still being used on special occasions!

On the second Day of this event, the Tea Institute showed its gratitude to its founder, Jason Cohen, by naming this Gallery of Asian Art after him. Samuel Li, the current director, gave the sign to Jason next to his delighted parents.

Jason Cohen graduated a few years ago and has now moved to NYC with the startup company he has founded, Gastograph, that specializes in analytical flavor systems. It aims at using rational measurements to taste and aromas of a big range of food and beverages (chocolate, coffee, beer, wine... and tea).

This is what their tool looks like when I use it to describe my latest Da Yu Ling 95K High Mountain Oolong from spring 2017:

I made this with the free App that exists both for Android and iOS. (Search: Gastograph) It can be a helpful tool to analyze the flavors of the tea, putting words and concepts on your feelings and remembering your experience. So, as you can see, Jason's company is deeply rooted in his Chinese tea tasting experience and his engineering background! And even if most of his customers are beer breweries and coffee makers, Jason continues to brew tea the same as he innovates, fearlessly: so many cups and such a little teapot!

During the first day, we learned that the Chinese achieved the first porcelain wares during the Eastern Han dynasty some 2000 years ago. The technique continued to improve with time. After the Eastern Jin (265-420), kilns in Jiangxi invented the saggar. Saggars are flame-resistant containers that protect the porcelain ware during the firing. This gives them a nicer and more even gloss and keeps the porcelain almost spotless.

White ceramics developed mostly in the North of China (ex: Ding ware from Hebei), but the climax of white porcelain was achieved in the south, in the kilns of Dehua in Fujian Province during the late Ming/early Qing period. French historian Albert Jacquemart (1808-1875) coined the term 'Blanc de Chine' (white from China) to call Dehua porcelain, a sign of Dehua's fame.

While we're focusing our study on porcelain tea cups, Dehua was actually even more famous for its sculptures of deities (ex: Guanyin with or without child).

This tall cup is a good example of the ivory (lard) hue of Dehua porcelain. The porcelain is rather thin and allows for the light to shine through the body. This reveals then a finely calligraphied Chinese poem!

This touches to key concepts of Chinese beauty dating back to the Sung dynasty: simplicity, refinement and purity. At first sight, the cup doesn't look that special, especially now that porcelain production has been industrialized. But instead of showing off the beauty of the calligraphy by painting with color, the artist chose to make it transparent and only visible under a direct light.

And, most amazingly, the tea tasted different when it had been poured from this cup. The taste was smoother, more refined and deeper. We could have used the Gastograph app to measure and analyze the difference! All the participants felt it. But it was no miracle or magic, just the result of using an antique cup made with natural ingredients, rested clay, wood fired in kilns with multiple chambers. For all these reasons, Dehua cups have the best impact on many teas (and Wuyi Yan Cha in particular) and we were lucky to experience it!

|

| The character 'wine' |

This small Dehua cup gives us a better explanation: most of such cups had dual use for wine and tea. We have proof for this in this cup: the characters Jiu and Cha were both written on the same cup!

|

| The character 'tea' |